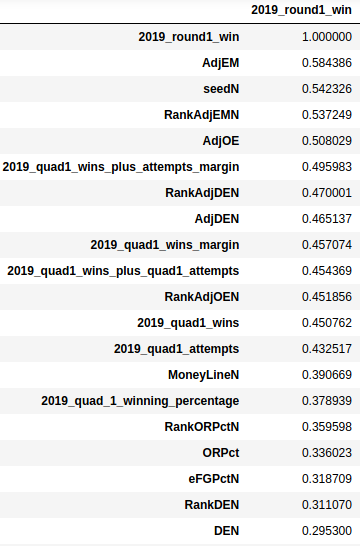

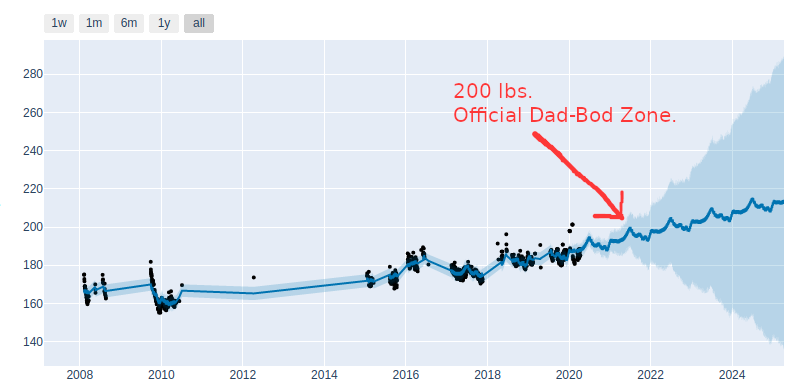

Like most people in America, I have the habit of occasionally stepping on the scale. Like most people in America, that scale has been increasing since 2008. I stepped on the scale over 1000 times in the last decade. I gathered up all this data and learned somethings about myself.

To continue building my Data Science skills, I used Python to wrangle and clean the data, visualize the data, predict likely and possible outcomes, and drew conclusions about my habits. To keep things short, I’ll jump right to conclusions *that apply to me* then go in depth below on analysis techniques, explanations, and next steps.

Conclusions

- Weight gain is an insidious monster.

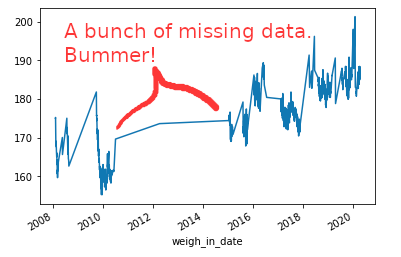

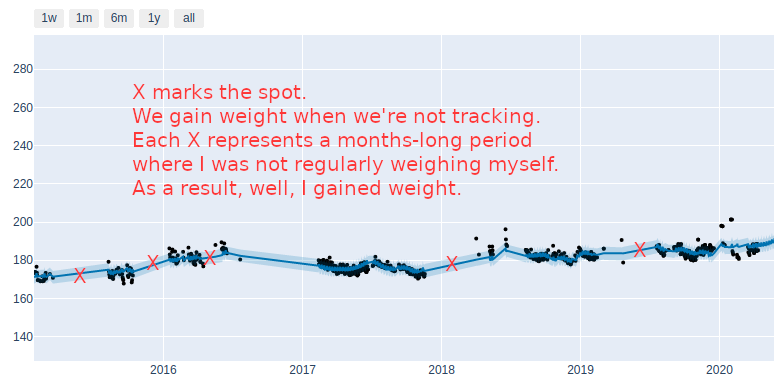

- Weight gain happens when we’re not looking (not stepping on the scale each day).

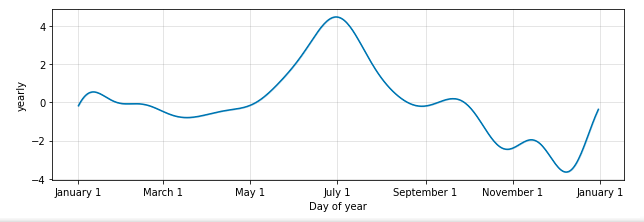

- Weight gain is seasonal.

- Wednesday is a pivotal day in the week for weight loss progress.

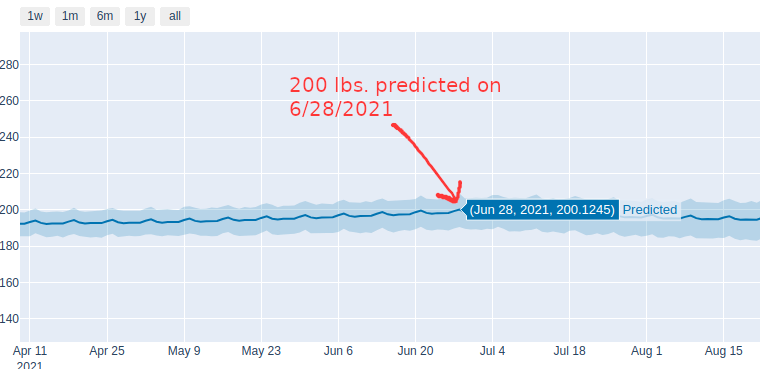

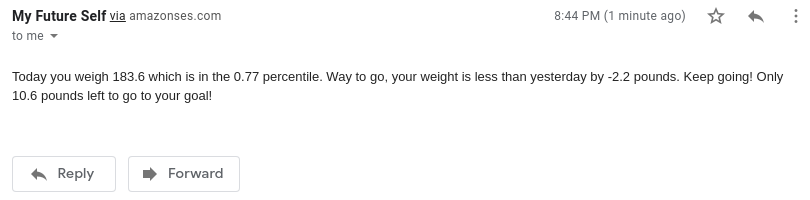

- I control my own destiny in the future. Update, in Part 2, I create a tool, My Future Self, to defeat the Dad-Bod

Wrangling the Data

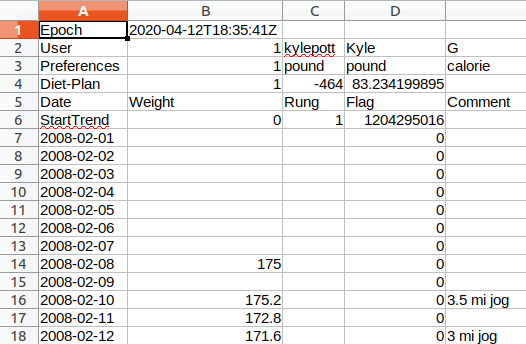

Since 2008 I used four different tools to track my weight: Hacker’s Diet Online, Weightbot (app retired, all data lost), MyFitnessPal, and TrendWeight. I was able to export, clean, and concatenate data from three of the four. Here’s the Python code I used to get a two column .csv with dates on the left and weights on the right. Update: see the GitHub repository below for the code. No judgment please, the code is not clean and could stand a good refactoring.

I started with the Hacker’s Diet data which was very poorly formatted (see the image below). Then I repeated the process with MyFitnessPal, which was better and finally TrendWeight which was in the best shape. TrendWeight is my current favorite tool for tracking weight as it has a tremendous amount of detail and also integrates seamlessly with my Withings wifi scale. The first part of this project was an art of renaming columns, removing null entries, removing repeating column headers, and selectively converting kg to lbs for the month or so I thought logging my weight in kgs would somehow be helpful (it wasn’t). Then I concatenated everything using an outer join to make sure I had only unique data and nothing repeating.

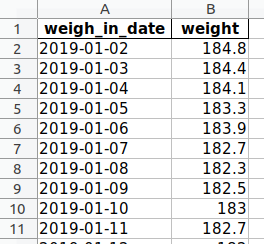

Now, we have a nice looking and easy to manage csv file with 1048 entries that we can work with for analysis and visualization.

Update: Originally, I included all the Python code in this post, but it got pretty lengthy. Instead, I created a new open source GitHub project if you want to download my work and use it yourself (GNU General Public License v3). Here is a direct link to a PDF of my Jupyter notebook if you’d like to follow my work step by step.

Describe the Data

After getting everything cleaned up, I started with a few basic techniques to learn more about the data.

Before coming down on myself too harshly, there are two bits of qualitative information to keep in mind. This data set covers 12+ years of my life from ages 23 to 35 and ranges 46.1 pounds from a low of 155.2 to a high of 201.3.

1.) I’ll start with a bit of an anecdotal observation. I think there is something to consider that a 23 year old male, me, just finishing college and getting started in the real world may not be done growing. I would imagine if we studied populations, very few people would weigh the same at 30, 40, 50+ as they did at 23. That’s not to suggest that everyone becomes more unhealthy as they age (adding body fat), but just an acknowledgement that a low weight I achieved in 2009 of 155 lbs. at age 24 may not be possible to achieve ever again. It just may not be possible. (more on this below).

2.) I started lifting weights regularly at the end of 2011. Unfortunately, the first four years of data from when I started lifting weights is gone and unrecoverable. However, I think it is fair to say that at a very conservative rate of growth, I could add 1-2 pounds of muscle every year. That might make a new plausible low weight for me to be 164-173. That assumes adding 1-2 pounds of muscle per year and that would be a *low* weight between the 10th and 30th percentiles of all weights I’ve ever weighed in my entire adult life.

Note: when I say I started lifting weights, intensity, effort, and consistency factor in. I competed in a powerlifting meet and achieved a 1000+ lb. total (bench, squad, dead lift). I’m not an elite athlete, but just to put in context when I say I might be able to add 2 pounds of muscle per year, it’s the backing to suggest this is plausible.

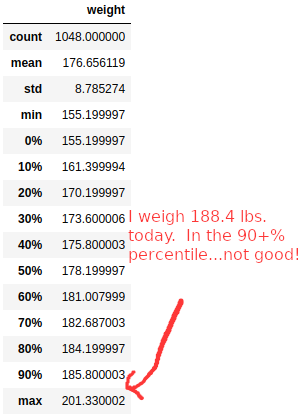

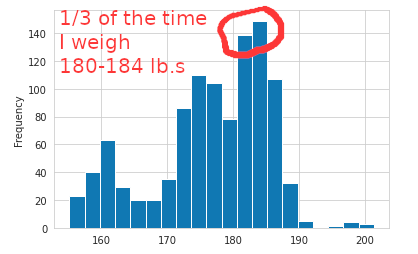

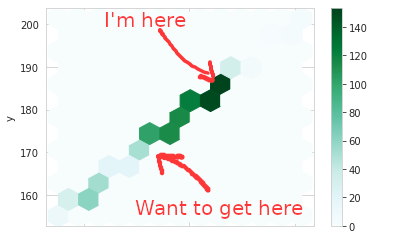

With such a wide range of possible weights, I thought it would be helpful to bin them and drop the data into a histogram. I learned that I weigh 180-184 nearly 1/3 of the time. This is good to know to help with the mental anguish of weight loss. Shouldn’t I weigh 155-160?! Actually, no I shouldn’t, because I almost never weighed that much (less than 6% of all weigh ins in 12 years). Also, it helps with setting a near term goal: get to a weight of < 180 and I’m already in the 50-60 percentile. Then get to 178 and I’m in the 40%, 175 and I’m in the 30%. We’re not talking huge numbers of pounds to lose here.

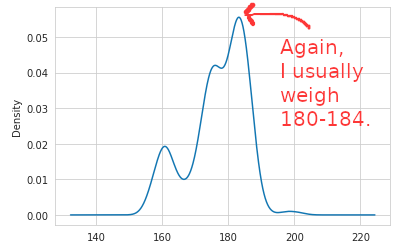

We can explain this concept in another way by showing a density chart. My greatest densities are in alignment with what we just discussed 180-184 lbs. then 179 lbs.

Cycles of Weight Gain and Loss

Whereas most people try to look better in their swimsuits, apparently I prefer to look thicker in my swimsuit. You know, to fill it out, I guess. After a modest downward tick after New Years, you can see a climb up that peaks around the 4th of July and then a steady weight loss through the end of summer, start of Fall, and just before the holidays. Then about a five pound weight gain through the holidays.

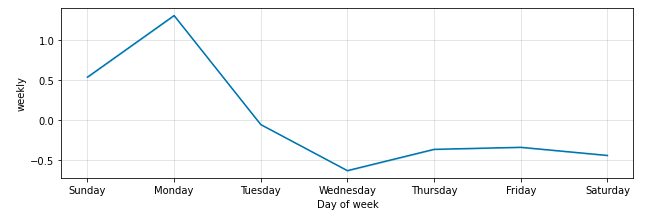

When we look at “seasonality” applied to each week, we learn more helpful insights about my habits. In order to reverse the trend here, I need to do better on Wednesdays and soften the weekend peaks. We have a bad data problem shown here. I have recorded very few weigh ins on Saturdays so that day of the week is not well represented. Presumably, because I eat a lot on Friday nights and I’m not all that interested in stepping on the scale at the start of the weekend. Another “now” habit to establish.

We Gain Weight When We’re Not Looking

There are a few exceptions, but unsurprisingly, long periods where I was not stepping on the scale resulted in prolonged increases in my weight.

Recipe for Success

I loved the book Atomic Habits. One of my top 10 favorite books. Author, James Clear, makes the case that to successfully establish new habits we need to break the trigger action down to the simplest, lowest level. Following that advice, here’s what I learned from this project that I will put into practice.

1.) Step on the scale every day. Even if I know I’m not going to like the results.

2.) Wednesdays are the day I will be most focused on my nutrition because it’s sets the tone for the week. No cheat days on Wednesdays.

3.) Set small goals, and keep working my way down the ladder. For me that means get to the next bin: 90th percentile is 185, 80th is 184, 70th percentile is 182, etc. until I arrive at the target range which is the 30% or 173. Update: Read Part 2 to see the system I set in place with a daily text message to remind me and give some encouragement.

Final Thoughts

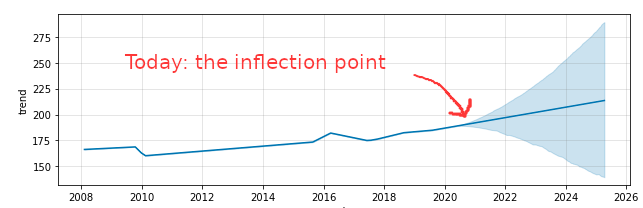

We control our own destiny – I meant for this post to be equally heavy on accountability and inspiration – we can achieve anything we set our minds to. Take a look at this last visual and look how the prediction splits toward either success and failure. There’s a quote I like that captures it:

You’re either growing or you’re decaying.

Unknown

(Potential) Next Steps

- I uploaded my Python code into GitHub if you’d like to geek out on this stuff yourself.

- One critique of my analysis is that weight (alone) does not tell the whole story (lean mass vs. fat mass). This is true and one of the reasons I love using the Withings scale with TrendWeight is that I have detailed lean/fat mass readings going back to 2018. I may dive into this in more detail, but I am somewhat skeptical about the accuracy of these readings. Nevertheless, it’s something to consider exploring.

- I am planning to tinker with the Withings API and try to create a more real-time “scorecard” to know what percentile I’m in and if I’m delaying (and ultimately defeating) the Dad-Bod date. Update: This is done. Read Part 2.

- If there’s enough interest, I’ll consider creating a web app that you can upload your own MyFitnessPal data and then get a similar set of visuals about your own data.

- Thank you to the Facebook engineers that created Prophet. I really enjoyed using it.